Joseph N. Agada

LLB (Olabisi Onabanjo University), BL (Nigerian Law School), LLM (Olabisi Onabanjo University), PhD (Babcock University), Lecturer Department of Jurisprudence and Public Law, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3459-8154

Adekunbi Imosemi

LLB, LLM, PhD (University of Ibadan), Professor of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice Administration, Babcock University

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2690-4242

Olubukola Olugasa

BA (OSUA), MA, LLB (UNILAG), BL (NLS), LLM (UI), PhD2 (BU), Professor of Law and Technology, Babcock University

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1763-2026

Edition: AHRY Volume 8

Pages: 3-27

Citation: JN Agada, A Imosemi & O Olugasa ‘The legal protection of boys and men against terrorism and banditry in Africa’ (2024) 8 African Human Rights Yearbook 3-27

http://doi.org/10.29053/2523-1367/2024/v8a1

Download article in PDF

ABSTRACT

Terrorism and banditry are two closely related crimes that involve the engagement of arms in violent attacks calculated to threaten, kill, destroy and annihilate a part or unit of a population with the intent to create a general atmosphere of fear and insecurity. There could be intimidation to achieve economic, religious and or political objectives. These violent crimes have resulted in the death of millions across the globe and caused untold hardship and instability in affected countries especially in Africa. The number of refugees arising from terrorism and banditry in Africa is taking astronomical dimensions even as governments are increasingly helpless. It would appear that the more commonly discussed victims of terrorism and banditry have been the girls and women considered the most and disproportionately vulnerable. Utilising the doctrinal research methodology, this article examines how these violent crimes affect boys and men in Africa by way of physical harms, psychological trauma and other life disruptions. It investigates the adequacy or otherwise of the legal protection in the hope of suggesting a sustainable and inclusive legal framework that factors the peculiarity of vulnerabilities of boys and men, especially in conflict-prone parts of Africa and ensuring their access to justice, rehabilitation and empowerment.

TITRE ET RÉSUMÉ EN FRANÇAIS

La protection juridique des garçons et des hommes contre le terrorisme et le banditisme en Afrique

RÉSUMÉ: Le terrorisme et le banditisme, deux formes de criminalité intrinsèquement liées, se caractérisent par l’usage d’armes et d’actes de violence systématiques visant à intimider, tuer, détruire ou anéantir des segments de population. Ces crimes, souvent motivés par des objectifs économiques, religieux ou politiques, génèrent une atmosphère de peur et d’insécurité généralisée. En Afrique, leur impact est particulièrement dévastateur, ayant entraîné des millions de décès, d’importants déplacements de populations, et une instabilité socio-économique accrue. Alors que les filles et les femmes sont fréquemment identifiées comme les principales victimes en raison de leur vulnérabilité perçue, les garçons et les hommes, souvent négligés dans les discours sur les conséquences de ces crimes, subissent également des préjudices graves. Ceux-ci incluent des blessures physiques, des traumatismes psychologiques, la conscription forcée, et des perturbations de leur rôle familial et social. En adoptant une méthodologie fondée sur le positivisme juridique, cet article examine l’impact spécifique du terrorisme et du banditisme sur les garçons et les hommes en Afrique. Il évalue l’efficacité des dispositifs juridiques actuels pour répondre à leurs besoins particuliers et explore les insuffisances d’un cadre de protection trop souvent focalisé sur d’autres catégories de victimes. L’étude propose des recommandations en vue d’un cadre juridique inclusif et durable, prenant en compte les vulnérabilités propres aux garçons et aux hommes, notamment dans les zones de conflit. Elle plaide pour des mesures qui garantissent leur accès à la justice, leur réhabilitation, et leur autonomisation, tout en renforçant les obligations des États africains à travers des réformes législatives, des mécanismes de protection spécifiques, et une meilleure prise en charge psychosociale des victimes masculines de ces crimes.

KEY WORDS: terrorism and banditry; insecurity; hostage; kidnapping; armed violence; forced recruitment; sexual violence; economic crimes; access to justice; Africa

1.1 Perspectives of terrorism and banditry in Africa

1.3 Why do people join terrorism and banditry?

1.5 Africa’s active terror groups and their country distributions

2 Boys and men as victims of terrorism and banditry

3.5 Incidents of terror attacks on boys and men across some jurisdictions in Africa

4 The legal framework for the protection of boys and men in Africa

4.1 The United Nations Convention on the Right of the Child

4.2 African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

4.4 Legal framework for the protection of men against terrorism and banditry in Africa

5 Findings, conclusions and recommendations

1 INTRODUCTION

The word ‘terrorism’ was noticeably used in the early 1790s to describe the terror approach employed by the French revolutionaries against their perceived enemies.1 The word has been associated with all kinds of negative references and meanings.2 Many times, even freedom fighters like Nelson Mandela have been tagged terrorists by the political class. While the United States of America had witnessed a series of domestic and international terrorism attacks, the commitment to prevent such re-occurrence did not emerge until after the 11 September 2001 attack.3

Not all African countries suffer from terrorism and banditry, but many countries on the continent are affected. The affected countries include Nigeria, Burkina Faso,4 Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Somalia, Kenya and Mali.5 Others are Niger, Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Burundi, Uganda, Togo, Rwanda, Morocco, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Benin, Sudan, South Africa, Mauritania, Angola, Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire.6 Sudan, Gabon and Angola are the least affected countries.7 It is important to mention that countries such as Ghana, Malawi, Madagascar, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Zambia, South Sudan, Botswana, Liberia, Namibia, Lesotho, The Gambia, Zimbabwe, and Equatorial Guinea are currently free from terrorism.8 This article aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the legal frameworks and protections available to boys and men in Africa who are affected by terrorism and banditry. It will delve into the specific challenges and vulnerabilities faced by this demographic, examining how existing laws and policies address their needs. It is structured into perceptions of terrorism and banditry.

1.1 Perspectives of terrorism and banditry in Africa

Several definitions have been propounded on terrorism. James Poland stated that the confusion over an acceptable definition is ‘the most confounding problem in the study of terrorism’.9 According to Shafritz, Gibbons and Scott in the early 1990s, ‘it is unlikely that any definition will ever be generally agreed upon’.10

Many researchers indicated to have accepted the assessment by Shafritz.11 While the debate rages on, researchers have learnt to by-pass the definition problem and focus their attention on other topics other than definition. Notwithstanding the inability of researchers of this topic to reach an acceptable definition, researchers have agreed that they cannot totally ignore the definition question. Adams Roberts agreed with this position when he stated:12

I do not share the academic addiction to definitions. This is partly because there are many words that we know and use without benefit of definition. ‘Left’ and ‘right’ are good examples, at least in their physical meaning. I sympathise with the dictionary editor who defines ‘left’ as ‘the opposite of right’ and then obliges by defining ‘right’ as ‘the opposite of left’. A more basic reason for aversion to definitions is that in the subject I teach, international relations, you have to accept that infinite varieties of meaning attach to the same term in different countries, cultures and epochs. It is only worth entering into definitions if something hangs on them. In this case (terrorism), something does.

Roberts’s position was right. The definition of terrorism is important to the entire study of the topic. An acceptable definition will allow researchers to develop shared views, methods, and approaches to the study and will help them to make recommendations on curbing the crime. In the absence of an agreeable definition, the study of the topic will be uncoordinated, fragmented, and unrealistic.13

Legally speaking, not all jurisdictions have definitions for terrorism. There are across jurisdictions what is referred to as shared features on the subject some of which are: the use of or threat of violence, creation of fear that is not limited or restricted to the immediate victims, but a larger population, use of arms et cetera. The extent to which it employs fear as a tool distinguishes banditry and terrorism from historically known war. However, this article considers terrorism from a legal perspective. It perceives terrorism strictly as a crime against the sovereignty of the state or states.

Terrorism can be said to be a violent crime involving the use of arms calculated to kill, destroy and annihilate a marked set or portions of a population of a state with the intention of creating a general climate of fear, insecurity, intimidation and failure in governance in an attempt to achieve economic, religious and or political objectives. Where it is for political objectives, it includes an attempt to topple the incumbent government or a radical change in the type or form of government.

Terrorism may mean the act of perpetuating violent crime either by an individual or a group of persons usually bonded by an ideology of the general public with the intention to create fear and send a message to the government.14 As stated earlier, the general aim of terrorists when they attack is to show not just their presence but their capacity and seriousness to the government. This accounts for why they usually will claim responsibility for their attacks afterwards.15

According to the Terrorism Act of the United Kingdom,16 terrorism is defined as ‘[t]he use of serious violence against persons or property, or the threat to use such violence, to intimidate or coerce a government, the public, or any section of the public for political, religious or ideological ends’. This definition is similar to that of the US. The US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines terrorism as ‘[t]he unlawful use of force or violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government or civilian population in furtherance of political or social objectives’.

The Nigerian Terrorism (Prevention) Act,17 as amended by the Terrorism (Prevention) Amendment Act,18 defines terrorism as an act committed with malice and intent to cause serious harm or damage to a country or international organisation. Such intent includes actions aimed at pressuring governments or international bodies to take or refrain from certain actions, intimidating populations, destabilizing or destroying fundamental structures, or influencing governments through intimidation or coercion. It also specifies that terrorism involves or causes attacks on people’s lives or kidnappings.19

Somalia’s ‘Terrorist Act’ adopted the 1999 International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism and its annexure. Terrorism in Somalia therefore means any act which constitutes an offence as involving any actions detailed in the treaties included in its annex. It also encompasses any acts intended to injure or kill civilians or non-combatants during armed conflict, with the aim of instilling fear in the populace or coercing a government or international organisation to either take a specific action or abstain from one.20

In like manner, Burkina Faso’s Repression of Acts of Terrorism 2015 shared the definitive view of the Nigerian Legislation. From the above definitions, it is clear that globally, there is an increasing awareness on what terrorism means. This position is buttressed by the fact that the UK, USA, Somalia, Burkina Faso, Nigeria and a host of other states have all proscribed virtually the same class of conducts and groups.21

The Global Terrorist index (GTI) report released towards the end of 2019 ranked Nigeria, for the fifth time running, since 2015, as the third most impacted by terrorism, globally and the most terrorised African country. However, Nigeria moved from being the most terrorised state followed by Somalia and Egypt in 2019,22 to being the third in 2021 and 2022 respectively.23 The implication of this is that Africa is terribly terrorised.

1.2 Banditry

On its part, Banditry can be said to mean the ‘actual or threatened use of arms (any instrument of force/coercion/violence) to dispossess people of their material belongings’.24 According to Ahmed, Tanimu Mahmoud, it means:

The occurrence or prevalence of armed robbery or violent crime. It involves the use of force, or threat to that effect, to intimidate a person with the intent to rob rape or kill. Banditry is a crime against persons. It has been a common genre of crime, as well as cause violence in contemporary African societies.25

Banditry in Africa has metamorphosed into an advanced continental security.26 Some organised criminals have seen banditry as a means of livelihood. In the same vein, terrorists often resort to banditry in an attempt to raise funds for their operations to gain advantageous bargaining positions. Kidnapping has become the usual and regular acts of bandits in modern day Africa.27

Terrorist groups engage in banditry and kidnapping for ransom while terrorism is ideologically motivated, banditry is often driven or motivated by economic considerations. Akogwu has argued that:

While the term ‘terrorism’ entails the premeditated use of violence by an ideologically motivated individual or group to create a general climate of fear in a population with the intention of bringing about a particular political objective, ‘banditry’ refers to economically motivated armed violence perpetrated by gangs driven primarily by the intention to extort, dispossess or plunder their targets -individuals, groups or communities.28

Secondly, while the primary goal of terrorists is to kill and destroy properties with the aim of sending a signal of insecurity and vulnerability, bandits operate for the immediate gain of the crime and use it as a means of extortion of citizens.

Bandits are less likely by their modus operandi to carry out targeted killings which are intentional targets of and strategies of terrorists. While terrorists have a broader leadership and organisational base with international synergies, bandits are often localised and operate in clusters.29 Furthermore, bandits have limited knowledge and interest in the use of sophisticated weapons while terrorists engage in military training of their members and increased sophistry of weaponry and theatre actions.30 While bandits are not known for using suicide bombing tactic, it is a usual signature of terrorists.31 While bandits do not operate media outfits, terrorist organisations usually have well organised and managed media outfits for propaganda and strategy.32

The above position and differences notwithstanding, it has been argued by some that there is no difference between terrorism and banditry as both crimes are often committed by the same set of criminals.33 Be that as it may, we believe that there are differences between terrorism and banditry.

1.3 Why do people join terrorism and banditry?

One of the reasons why many people voluntarily go into terrorism and banditry is to vent their grievance against the system. It could be the political or economic system. Peter Tosh a Reggae artist in his song ‘Justice’ said that asking for peace where there is no justice is needless and that once there is justice, every crime present in the society will vanish in a short while. It has been shown that many young people who leave Europe to fight as insurgents are youths who for one reason or the other, are unhappy with the governments.34 For this group, there are no economic considerations, but a chance to avenge a perceived injustice.

For some others, it is because they are disillusioned and have lost self-belief, confidence and courage. Consequently, they are constantly in search of what will fill the void of self-esteem and lack of courage.35 This is one of the reasons why many youths join cult groups too. They are in search of self-esteem, security and protection.

Some people join terrorists and bandits mainly for economic gains. Some see it as a way of catering for their families and meeting personal needs. A research conducted in Somalia showed that those recruited into terrorist organisations particularly from the local communities join them mainly for economic benefits. 27 per cent of the respondents said they joined al Shabab for financial reasons. 15 per cent said their reason was religious and 13 per cent said they were forced into it.36

For yet others, the only motivation is the belief God-imposed a duty to defend their religion against other religions or influences considered taboo or alien to the terrorists’ religion.37 The quest for power and control forms the basis for why some other persons venture into terrorism. A typical case is the situation in Afghanistan where the terror groups have indulged in and fought for control of the country for decades and finally succeeded in what is currently referred to as the rule of terrorists in the country.

1.4 Types/forms of terrorism

Study subjects like terrorism are better classified based on observed typologies.38 One of the popular bases for classification recognises three basic types of terrorism namely: revolutionary terrorism, sub-revolutionary terrorism, and establishment terrorism. Although this classification has been challenged, it is helpful in the understanding and evaluation of terrorism.39

Revolutionary terrorism is the most common form of terrorism. Here the terrorists’ goal is the complete abolishment of the political order and to replace the same with the system that agrees with the ideology.40 Sub-revolutionary terrorism is not so common.41 The terrorists here do not seek a total change or abolishment of the existing system or order, but a modification. An example of this type of terrorism is the case of ANC and its campaign to end apartheid in South Africa which was tagged terrorism by the white rulers.

Establishment terrorism also referred to as state or state-sponsored terrorism is used by governments -- or more often by factions within a conflicting system of government.42 One clear feature of establishment terrorism, unlike others, is secrecy. Governments that perpetuate this type of terrorism, keep their plans away from their citizens to avoid regional and international sanctions.43

There is another popular typology which deals with the classification of terrorism by their operational level rather than their goals.44 Under this heading, there are mainly four types of terrorism and banditry namely: State-sponsored terrorism, dissident terrorists, international terrorists, and terrorism for religious purpose.45

1.5 Africa’s active terror groups and their country distributions

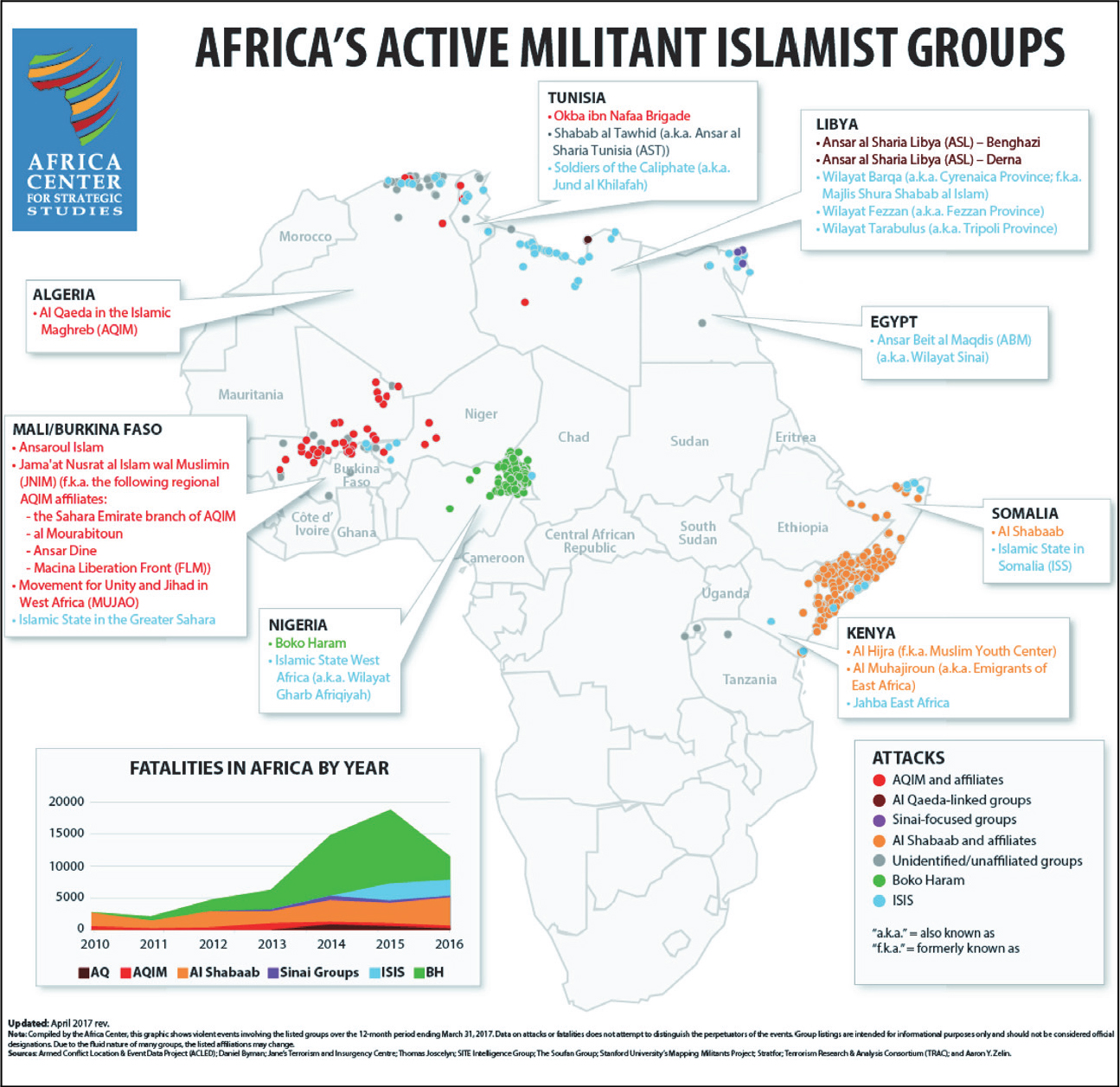

It has been posited that across the African continent, there are 21 terror groups with presence in 54 countries that are very active with well published activities, namely:

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansaroul Islam, Jamaat Nusrat Al-islam Wal Muslimeen, the Movement for Monotheism and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Boko Haram, Islamic State West Africa, Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade, Shabab Al-tawhid, Soldiers of the Caliphate, Ansar Al-Sharia (Derna), Ansar Al-Sharia (Benghazi), Wilayat Barqa, Wilayat Fezzan, Wilayat Tarabulus, Ansar Bait

Al-Maqdis, Al Shabaab, Islamic State in Somalia, Al Hijara, Al Muhajiroun, Jahba East Africa.46

The above terror groups and their country distributions are as shown in the distribution map below with the exception of Mozambique where the complexity of the conflict has made it difficult to identify others apart from the main ISIS-Mozambique, also known as al-Shabaab:47

2 BOYS AND MEN AS VICTIMS OF TERRORISM AND BANDITRY

Among writers, there has been a consensus on violence targeted at a particular gender,48 evidence exists that men and women have been specifically selected as targets of terrorism because of their gender for various reasons.49 For example, reports have shown that men and boys have been murdered in their numbers, females and even girl children have been the victims of terrorism and banditry too,50 and both genders have come face to face with gender based violence.51 The question therefore is why are terrorists and bandits choosing boys and men as victims of their crimes? Some of the reasons are as follows.

Enemy boys and men can be selected for abuse and terror attacks as a way to end the group’s heritage and future.52 Boys and men can also be targeted by terror groups in an attempt to leave the entire population vulnerable, weak and defenceless against future attacks and to make eventual total take-over of the affected territory less combative.53 Using this approach, terrorist groups have taken over several territories with the men and male children annihilated, leaving no room for any revolt in the nearest future. The women and girls are at the mercy of such terror groups.54

Another reason why boys and men may be specifically targeted by terrorists is to immortalise the legacy of the terrorists by raising generations of terrorists after them. With this philosophy in mind, terrorists embark on kidnapping and forced recruitments of boys and young men.

Teens are particularly vulnerable to this approach of extremists using mails that promise to meet a variety of needs by the young ones it is targeted at. It could be financial, psychological, or religious needs. ISIS and al-Qa‘ida have repeatedly adopted this method of recruitment to woo minors using online platforms. For instance, in the month of October 2018 al-Abd al-Faqir Media Foundation, a pro-ISIS media outfit -- launched its first Arabic-language magazine titled ‘Youth of the Caliphate’, aimed at young supporters who may share ISIS ideology.55

The next question to be answered is how are boys and men victims of terrorism? These can happen in several ways, namely: through targeted elimination or annihilation by terror groups. This can be done with several reasons in mind as explained earlier. The second way in which men and boys can and have become victims of terrorism is through forced recruitment into terror armies. There have been stories about many terrorists confessing upon arrest that they were coerced into the terror groups at the risk of being killed. A report titled ‘How Boko Haram is Forcefully Recruiting Cameroonian Boys’56 showed how militants of the dreaded Boko Haram group snatch young boys in Cameroon, from across the border with Nigeria, to force them into the sect. According to the report, numerous villages in the area were cleared out and schools torched by the terrorists even despite the presence of security operatives. Some residents recounted how Boko Haram raided villages during the daytime. Indoctrination is a strong tool at the hands of the terrorists against their coerced victims.57

In furtherance of its position against terrorism, the International Criminal Court in the Hague has proscribed the engagement of minors particularly persons who have not attained the age of 15 into the army or making them engage in armed conflict as a crime. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that all parties should ensure to guide against the engagement or combat use of minors.58 The above position notwithstanding, the recruitment of boys and men into terror groups have continued unabated. One of the ways by which this is done is by deceiving their victims into believing that they are going for Islamic training.59 Evidence showed that between 2005 and 2020, more than 93 000 children were recruited into all kinds of armed groups including terror groups.60

3 THEORIES OF TERRORISM

3.1 Political theory

Under this theory, the main consideration for the terrorist groups is the quest to gain political power or control over territories.61 A ready example is the case of Afghanistan where the militants fought the US and its incumbent government with the aim of wresting power from them and achieved it in 2021 with the exit of American forces. The militants currently run the government of the country with tails of woes.62

Many times, terror groups have argued that their decision to take up arms against the government is their way of protesting against misrule and corruption by government officials and undue foreign interest in the natural resources of their countries among others.63 It has been argued that Anarchism was the ideology that gave rise to political agitations.64 For example, the theory teaches the six steps to undermining the ‘social structure for revolutionary change’.65 states: ‘Wipe out the intelligent and the vigorous persons of the society then, abduct the wealthy community for ransom for your financial strength, join the group of politicians and take out their secrets, help the criminals of that society to make your own militants ...’ Carlo Pisacane propounded the idea of bombing and using propaganda to achieve political goals. Karl Heinzen and Johann Most on their part consented to the employment of weapons capable of wrecking massive damage to lives and property for the same purpose while Claudius Konigstein agreed with the teaching that innocent persons, crowded places and economic infrastructures be targeted to achieve a violent revolutionary goal.66

3.2 Economic theory

The position of this theory is that one principal motivation of terrorism is the economic gains. There abound instances where alleged terrorists have confessed that they decided to join the terror groups because they were promised good financial gains which will in turn allow them to take care of their families and meet personal needs. For the proponents of this theory, if the state wants to curb terrorism, it should concern itself primarily with ensuring a good economy and equal economic opportunities for its citizens.67 Here, the state should pursue economic policies that are capable of giving the people economic prosperity and sustainable development. While it is the position of this paper that a country’s economic state should not be a ground for commission of crime, it is common knowledge that involvement in crime has often been motivated by these factors.

3.3 Religious theory

The link between religious discipline and extremism is a strong one. About half of all the deadly terror sects across the world have religious ideologies.68 They see the armed conflict particularly terrorism as a way of homage to God and defending their allegiance. They believe it is jihad (holy war) which they must fight for God and be ready to die for if they truly love and believe in God. To them, it is a demand placed on them by God and for which they shall be rewarded heavily in this world and the world after.69 Influenced by this indoctrination that comes through a system of education, they can gladly engage in suicidal terror attacks using bombs and other weapons against other religions and governments.70 These terrorists see religious secularism, moderni-sation and westernisation including western education as vices and enemies that must be defeated at all cost. This is the case of Boko Haram in Nigeria and ISIS.

3.4 Rational choice theory

From this perspective, terrorism is a calculated violence in pursuit of certain objectives considered rational and justifiable when compared with the risks involved. Terrorism has been known to have some political undertone with goals71 including the removal of a regime72 or national independence.73

3.5 Incidents of terror attacks on boys and men across some jurisdictions in Africa

It was reported that Boko Haram insurgents murdered no less than 43 farmers who were working on a rice farm in Maiduguri on Saturday the 28 November, 2020. The terrorists bound their victims and slit their throats with knives. 43 dead bodies were recovered, along with six others with fatal injuries. More bodies were recovered later raising the death toll.74

A truck bomb attack in Mogadishu capital of Somalia on Sunday the 15 October 2017 claimed at least 500 casualties and over 300 deaths involving mainly men and who were out to fend for their families.75 The scale of the attack made it a matter of grave concern and one that the world will not forget in haste.76

In Algeria, while the government appears to be doing so much and is fully committed to the fight against terrorism, there are still reports of attacks here and there with casualties. On 14 October 2021, there was a report of the murder of a soldier with use of an improvised explosive device (IED) whilst the soldiers were on patrol duty at Tlemcen. On 6 August 2021, two military men were also murdered with the use of IED while on a mop up duty in Ain Defla. Two soldiers were also killed on 2 January 2021 while on duty at Tipasa and several other reports.77

According to a report published in March 2019 by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)78 continuous conflict has resulted in the displacement of about 115 310 persons internally in Burkina Faso alone. The regions most affected include the Sahel, Centre-Nord, Nord, and East regions, where the terrorists have concentrated their attacks. This shows that the impact of terrorism and banditry on boys and men are not just in their coerced recruitment and killing, but in injury and displacement and several other ways.

On 3 June 2022, it was reported that at least 50 persons were killed in an attack linked to al-Qaeda and ISIL (ISIS) in Northern Burkina Faso. The attackers were said to have struck at night in the province of Seno.79 Again on 10 June 2022, it was reported that 11 Burkinabe military policemen were murdered in northern Burkina Faso by terrorists after their base came under heavy attack.80

In Sudan, on 9 December 2014 it was reported that a gun man later identified as a member of an Islamic militant group referred to as Takfir wal Hijra, walked into the mosque in the village of Garaffa, outside Omdurman, the twin city of the capital Khartoum during prayers, and opened fire on the worshippers using an automatic rifle killing tens of worshipers. He was later killed after all entreaties to him to surrender proved abortive.81 The Sudanese Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, was said to have survived a terror attack at the capital on 9 March 2020.82

There is no recent data of terror attack on Angola83 The last terror attack in Angola appears to be the train attack of 2001 where a train was derailed and 250 persons on the train were killed.84

For banditry, data showed that from 2011 to 2020, persons in Nigeria paid not less than US$18.34 million (7 billion) ransom to bandits for the release of their loved ones.85 In the first half of 2021, a total of 2 371 persons were reportedly taken hostage and the sum of about US$23.84 million (N10 billion) demanded for their release in Nigeria.86 A latest report has shown that the sum of N653.7 million ($1.2 million) was paid as ransom for kidnapping in Nigeria between July 2021 and June 2022.87 Banditry is thriving in Nigeria more than any other African country.88

4 THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE PROTECTION OF BOYS AND MEN IN AFRICA

While one may not be able to point to a law that specifically designed in its entirety to solely protect boys and men against terrorism and banditry in Africa, there are laws whose provisions protect boys and men across various jurisdictions. These include the bill of rights in national constitutions, national, regional and international human rights instruments, and the African Youth Charter among others. Additionally, there are laws with general provisions for the protection of citizens against terrorism and banditry. For example, the Anti-Terrorism Act of Uganda,89 the Somalian Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism Act,90 Burkina Faso’s Repression of Acts of Terrorism,91 the Nigerian Terrorism (Prevention) Act 2022 and other legislations against terrorism in Africa, all have general provisions protecting citizens including boys and men. The laws all made general provisions for the protection of the citizens of each country against acts of terrorism. We shall proceed to consider some of the laws with provisions protecting boys and men against violent crimes and recruitment into armies and armed conflicts.

4.1 The United Nations Convention on the Right of the Child

The United Nations Convention on the Right of the Child (the Convention) was adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by the General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. It entered into force on 2 September 1990 in accordance with the provision of article 49.

Article 1 of the Convention defines a child to mean ‘every human being below the age of 18 years’. This definition accords with the position under the Nigerian Child Rights Act and that of other African countries.

Article 3 of the Convention provides that ‘in all actions in relation to a child in any member state the best interest of the child shall be primary consideration’.92 Article 6(1) provides that ‘States Parties recognise that every child has the inherent right to life’. Article 6(2) provides for the ‘child’s right to survival’. Consequently, any act of terrorism or banditry that negatively impacts a child’s right to life and survival is a violation. Article 9(1) states:

States Parties shall ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents against their will, except when competent authorities subject to judicial review determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child. Such determination may be necessary in a particular case such as one involving abuse or neglect of the child by the parents, or one where the parents are living separately and a decision must be made as to the child’s place of residence.

This Article serves to protect the child against any act including terrorism and banditry that is capable of causing an unlawful separation between the minor and his/her parents.

Article 13(1) envisages a situation where a child is kept in custody on the allegation of wrongs and provides that the child must be given right to fair hearing before any decision is taken.

Apart from the right to fair hearing discussed above, the child by virtue of articles 14, 15, 16 and 17, is guaranteed the rights to freedom of thought and religion, right to peaceful assembly, right to private and family life. All these serve to protect the child from all forms of violent acts or crimes. Specifically, article 19(1) protects the child against all forms of physical or mental violence, exploitation, abuse and injury.93 Taking this further, article 38(3) provides against the recruitment of children below the age of 15 into the armed forces by states. The article provides:

States Parties shall refrain from recruiting any person who has not attained the age of 15 years into their armed forces. In recruiting among those persons who have attained the age of 15 years but who have not attained the age of eighteen years, States Parties shall endeavour to give priority to those who are oldest.

This provision aligns with the position of the International Criminal Court stated earlier. The direct implication of this is that the engagement of minors by terror groups and bandits is a violation of this Convention.

4.2 African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

The African Charter on the Right and Welfare of the Child was adopted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in July 1990, and became effective on 29 November 1999. The Charter is a working document among African nations. By virtue of article 1, the Charter places responsibility on all parties to do all within their constitutional powers to protect the child in their various states.

Just like the UN Convention on the Right of the Child, the Charter defines a child in article 2 as ‘... every human being below the age of 18 years’. Article 4 affirms that ‘the best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration’ when dealing with any issue involving a child. This provision runs through virtually all statutory documents on ‘the right of the child’ across the world.

Article 22(1)-(3) seeks to protect the child from every form of armed conflict. It frowns at the recruitment of children into the army or any armed conflict. This necessarily will include terror groups and banditry.

Articles 27 and 28 protect the child from ‘sexual and drug abuse’. In other words, no child should be subjected to any form of sexual and drug abuse. These are common habits of terrorists and bandits who recruit children into their groups.

4.3 The Child Rights Act 2003

This is a Nigerian legislation on the rights of the child. The Act opened in section 1 with a categorical provision to the effect that in all situations when an action is to be taken in relation to a child, ‘the best interest of the child shall be the consideration’.94

Section 3 of the Act applies the provisions of Chapter 4 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended) to the Child Rights Act and every child. This means that every child in Nigeria is entitled to all the rights enshrined in chapter 4 of the Constitution. This is a laudable provision shared by this Act with the UN Convention on the Right of the Child and the African Charter on the ‘Right and Welfare of the Child’. In addition, section 4 bestows on every child the right to survive and develop.

Sections 21-23 of the Act prohibit child marriage or betrothal of any kind. This is another protection of the child both male and female from being forced or coerced into such unions like we see and read about terrorist organisations who forcefully marry out minor captives who are then subjected to all kinds of sexual abuses like the case of Chibok girls who returned from captivity with babies and pregnancies.

Section 26(1) and (2) of the Act titled ‘Use of children in other criminal activities’ provides:

No person shall employ, use or involve a child in any activity involving or leading to the commission of any other offence not already specified in this Part of the Act. A person who contravenes the provisions of subsection (1) of this section commits an offence and is liable on conviction to imprisonment for a term of fourteen years.

This is an outright criminalisation of the recruitment of children whether boys or girls into any criminal act including terrorism and banditry. Section 34 prohibits the recruitment of children into the army.95 Section 27 went on to criminalise the removal of any child from the lawful custody of his/her parents with various sanctions depending on the intention of the criminal.

4.4 Legal framework for the protection of men against terrorism and banditry in Africa

As stated earlier, a study of the anti-terrorism laws of African countries show that there are no laws with specific provisions protecting men against terrorism and banditry. However, the laws of the various African states on terrorism and other violent crimes have provisions for the protection of the citizens generally. The provisions of the laws notwithstanding, men and children have continued to be forcefully recruited by various terrorist groups. Many of these forcefully recruited men and children have been killed by either the terrorists, bombs strapped to their bodies or as a result of confrontation with state forces.

The Act in article 7 punishes acts of terrorism with imprisonment for life. Article 14(7) criminalises the recruitment outside of the authority of the state to form armed groups other than the army and police. This Article can be taken to protect boys, girls, men and women against being recruited into any terror group in the country. It is the argument of this paper that the capital punishment imposed by article 7 will serve the purpose of deterrence in the fight against terrorism and banditry.

The Uganda Anti-Terrorism Act, 2002 passed on 21 May 2002, which took effect on 7 June 2002, provides insight into this discussion. The law in an attempt to curb terrorism imposes sanctions on anyone who publicly professes, instigates, supports, finances or executes acts of terrorism. The law also imposes sanctions on anyone who convenes or attends any meeting intended to serve a terrorist purpose. To this effect, the law authorises the interception of the correspondence of and the surveillance of persons suspected to be involved in acts of terrorism.

Consequently, section 7 punishes terrorism with the death penalty. The jurisdiction of the court is as defined in section 4 of the Act. The second schedule to the Act proscribes ‘the Lords’ Resistance Army, the Lords’ Resistance Movement, Allied Democratic Forces and Al-qaeda’ as terrorist organisations in the country.

Legislation in Nigeria is the Terrorism (Prevention and Prohibition) Act, 2022. Section 1 of the Act set out its objectives in paragraphs (a) to (f). Sections 11-24 of the Act spells out the various acts that amount to terrorism and their sanctions ranging from 20 years imprisonment to death depending on whether death occurred in the course of the crime.96

Noticeably, section 24(1) and (2) provides: The implication of the above is that hostage taking which is a crime of both terrorists and bandits is also punishable under the Act.97

In our opinion, seeking special legal protection for women and children (boys and girls) against terrorism and banditry, seem logical, but to argue that men especially the healthy and strong deserve any special legal protection against terrorism and banditry other than what is provided generally in the law, will amount to begging the question of legal protection. How can such an argument fly in the face of the contest that terrorists and bandits are usually men?98 Our study showed that despite the efforts of the International Criminal Court and the UN’s Convention on the rights of the child, none of the legislations has any particular provision to protect the children and women. The Terrorism (Prevention) Act,99 (just like the laws across the other jurisdictions), made various provisions with respect to terrorism including hostage taking in line with section 24 pointed out earlier.100

Despite the existing legal frameworks, governments of various countries in Africa are working using administrative instruments to equally combat the scourge of terrorism and banditry across Africa. Their efforts include the purchase of more weapons in the fight against these crimes, training and retraining of officers fighting these crimes, gathering of community intelligence etc. While countries like Angola, South Africa, Libya and a host of others affected by terrorism and banditry appear to be doing so much and recording successes, the same may not be said of the Nigerian government which has been accused severally of complacency on the issue of terrorism and banditry in Nigeria.101 The truth is that Nigeria needs to do much more to truly defeat insurgency.

5 FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This paper finds that boys and men are direct victims of terrorism and banditry across African states either as persons killed, injured or rendered orphans and widowers or victims by way of coerced recruitment into terrorism and banditry.102 11,000 men were reported killed in Zamfara state by armed bandits alone as at the first quarter of 2019. Several women were widowed due to the killing of their husbands, who served as the breadwinners of their families.103 It is our finding that despite the precarious position of boys with respect to terrorism and banditry there is no particular legal protection for them against the crimes the stand of the International Court of Justice and United Nations notwithstanding.

It further finds that there are a number of factors that fuel terrorism and banditry across Africa. Such factors include bad governance, external political influence, bad or poor economy, brazen corruption by leaders, religious extremism and indoctrination among others,

This article examines the concept of terrorism and banditry and how they affect boys and men in Africa considering the strategic roles that boys and men play in the safety and perpetuation of societies. The various theories of terrorism and banditry were examined along with the legal framework on the subject matter. The paper argued that there are no specific legislations solely dedicated to the legal protection of boys and men against terrorism and banditry in Africa. This, the article posits, is rightly so because the existing legislations and conventions have provisions for the protection of citizens (including boys and men) against terrorism and banditry. The paper further argued that while there may be no particular need for any special provision in our laws to protect boys and men against terrorism other than the general provisions in the law, the position of the International Court of Justice and the United Nations calling for heavier sanctions for persons who recruit or encourage the recruitment of minors into terrorist groups or as bandits should be adopted by all African countries and reflected in the laws.

Towards better legal protection of boys against acts of terrorism and banditry, this article makes the following recommendations:

Rather than the current situation in which governments across Africa are negotiating with terrorists and bandits or criminals which step is unrealistic and only temporary, the governments should ensure that the illiterate citizens are educated, and that jobs are created to engage the unemployed youths. This follows the backdrop that illiteracy and youth unemployment coupled with poverty have been at the centre of banditry and terrorism. Here in Nigeria, we have heard the accounts of young men who are recruited into banditry and terrorism with a promise of what an average citizen will consider ridiculous. The victims have taken such offers and have become tools for hostage taking and wanton destruction of lives and properties. Some suspects who have been caught have confessed to receiving as low as N20 000 for their involvement in banditry.

As aptly suggested by the International Court of Justice and the United Nations, there should be copious provisions in the laws across Africa to impose heavier sanctions on persons who recruit or encourage the recruitment of minors into terrorism and banditry or any criminal set whatsoever. It is the belief of this paper that heavier sanctions will serve the purpose of deterrence and discourage those who are planning to go into banditry or terrorism. African states must be seen to be serious and intentional about curbing the scourge of banditry and insurgency without any element of political colouration. African leaders need courage, equity and fairness as some essential steps that are needed to be taken to end the glaring security challenges in the nation.

This article further recommends that the intentional neglect of borders, towns or communities in the provision of socio-economic infrastructures should be replaced with actual development of the communities and effective security presence and occupation along the borders and forests and reserves. As posited by John Sunday Ojo and others104 weak border security and the existence of ungoverned spaces have contributed to the rise of banditry and insurgency in Africa. The governments must ensure that no part of their territories including forests is left in the hands of bandits and terrorists. There should be constant security patrol along the borders. There should be provision of security around schools knowing fully well that they have become soft targets for both terrorists and bandits to either make a statement or raise money from ransom. The governments across Africa should have verifiable security plans for the protection of lives and properties which are the basic responsibilities of any government.

Governments in Africa should address the issues of injustice by strengthening the administration of the justice system. This way, citizens will have more confidence in the systems and desists from self-help as a means of addressing injustice. Lately in Nigeria, the politicians have become so emboldened and quick to ask citizens who complain of injustice in the electoral system to go to court. Many have argued that this is so because the politicians have compromised the judiciary. This accounts for why the judiciary has lost the trust of the people who have resorted to self-help in many instances or forget about the matter all-together. This does not work any good for a state as it will encourage all forms of unrest including banditry and insurgency.

The governments should ensure the constant training and retraining of the officers engaged in the fight against insurgency and banditry. The Law enforcement agencies should be encouraged to engage in more detailed community intelligence gathering to help frustrate attacks rather than the current reactive measures. From the experience here in Nigeria, our law enforcement agents are more reactive than preventive in their fight against banditry and insurgency. The place of intelligence gathering in curbing banditry and insurgency cannot be overemphasised. The welfare of the security agents involved in the fight against banditry and terrorism should equally be taken seriously by the government officials and the heads of the various security agencies.

There should be state policies and legislations monitoring religious institutions and their teachings to guide against indoctrination and extremist tendencies. Drawing inspiration from Kenya, religious institutions should be regulated by the government to guide against indoctrination of its adherents. One recalls that what is today known as Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, started as a religious gathering organised by a self-acclaimed Islamic cleric who used the illiteracy and poverty of the people who gullibly followed him to indoctrinate them. Religion has become a tool used for recruiting unsuspecting adherents into crime and it should be checked. The governments of various African states should develop strategies and programmes that will disarm terrorists and change their ideologies without necessarily offering them amnesty. The current practice where terrorists are given amnesty and even recruited into the military as we see in Nigeria, is not safe for national security. There should be well intended programmes targeted at reorienting arrested terrorists and a massive campaign against the crimes in the domains where they are perpetuated to discourage others from joining the crime.

African leaders should evolve themselves and be given to good governance. They should shun the attitude and quest to remain in power till death and encourage youth participation in government across board. The unbridled quest by African leaders to remain in office till death has led to various uprising and security threats in the continent. African leaders should learn to respect the constitutions of their various countries and ensure smooth transitions whenever their tenure laps.

Negotiation and payment of ransom to bandits and terrorists should be criminalised across Africa. This recommendation is coming on the hills of the fact that banditry is growing daily across Africa because of the payment of ransom. It has been repeatedly shown that the payment of ransom to bandits and terrorists has further enhanced their operations and given them access to more alms. It has equally led to the rising of other groups of terrorists and bandits who now see the crimes as highly profitable ventures. In Nigeria, banditry and hostage taking is on the rise because of the humongous ransoms that are paid to bandits on daily bases. Several bandits suspects have confessed that they formed their own kidnapping gangs when they were told of the amounts being collected as ransoms by other groups and the ease with which the ransoms are collected.

Governments across Africa should be bold to proscribe any criminal groups using the modus operandi of terrorists like the bandits in Northern Nigeria. In Northern Nigeria, there are various groups overseeing and levying several communities. They dictate to the farmers when the farmers can go to their farms and when they should remain indoors. They charge various sums and until they are paid, such communities are held under siege. The same thing applies in South Eastern Nigeria where some militias have designated Monday as a sit-at-home day and those who go out to work have been killed and maimed. Several law enforcement agents have been killed without provocation. It is the position of this paper that the government should have no difficulty whatsoever designating such groups as terrorist organisations.

1. JP Jenkins ‘Terrorism’ Britannica on politics, governance and law https://www.britannica.com/topic/terrorism (accessed 27 August 2022).

2. A Silke, ‘The study of terrorism and counter terrorism’ available at https://www. researchgate.net/publication/326849404_The_Study_of_Terrorism_and_Coun terterrorism/link/5b6968f9a6fdcc87df6d6a52/download (accessed 8 August 2022).

3. JW Maze ‘With liberty and justice for all: An examination of the United States’ compliance with rule of law as it relates to domestic and international terrorism’ Masters thesis, Wright State University (2018) 36.

4. Studies have shown that Burkina Faso’s government only controls 60% of the country’s territory and the rest 40% is under the control of terrorists and bandits. See Mahamadou Issoufou, former president of Niger who was appointed by ECOWAS as a mediator to Burkina Faso, Al Jazeera news of 18 June 2022. Reutershttps://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/18/state-controls-only-60-per cent-of-burkina-faso-mediator (accessed 14 September 2022).

5. Africa Centre for Strategic Studies referred to by Bridget Boakye, ‘Terrorism in Africa: 21 active militant groups on the continent in 2018’ https://face2 faceafrica.com/article/terrorism-in-africa-21-active-militant-groups-on-the-conti nent-in-2018 (accessed 30 August 2022).

6. Satista ‘Terrorism index in African countries as of 2021’ https://www.statista. com/statistics/1197802/terrorism-index-in-africa-by-country/(accessed 13 Sep-tember 2022).

11. The assessment and or position is to the effect that rather than dissipate energies on the seemingly unresolvable issue of definition, researchers should pay more attention to the other issues involved in the study of terrorism and how the crime affects humanity. This way, they can make recommendations on how to stop the menace. It is taken that certainly within each society people have an idea of conducts or acts that are categorised as terrorism. The sense often is that while one might not be able to define the term terrorism absolutely, he/she has an idea of what it is and can recognise it when seen.

12. As quoted in A Roberts, ‘Can we define terrorism?’ Oxford Today, http://www.oxfordtoday.ox.ac.uk/archive/0102/14_2/04.shtml (accessed 29 August 2022

13. A Merari ‘Academic research and government policy on terrorism’ (1991) 3 Terrorism and Political Violence 88-102. She argued that repeated occurrences of the same phenomenon are the basis of scientific research. In the case of terrorism, however, there is hardly a pattern which allows generalizations. Clearly, the heterogeneity of the terroristic phenomena makes descriptive, explanatory and predictive generalizations, which are the ultimate products of scientific research, inherently questionable

21. See sec 2 of the Nigerian Terrorism (Prevention) Act, sec 3 and Schedule 2 of the UK Terrorism Act, American Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act of 2022

22. Global Terrorism Index: ‘Top 20 most terrorised countries in Africa, 2018’ available at https://talkafricana.com/global-terrorism-index-top-20-most-terro rised-countries-in-africa-2018/ (accessed 29 August 2022).

23. Global Terrorism Index available at https://moroccantelegraph.com/news/global -terrorism-index-2022-morocco-among-the-least-affected (accessed 29 August 2022).

24. AC Okoli & A Ugwu ‘Of marauders and brigands: scoping the threat of rural banditry in Nigeria’s North West’ (2019) 4(8) Brazilian Journal of African Studies 201-222.

25. See AT Mahmoud ‘Banditry dynamism and operating pattern of crime in northwest Nigeria: a threat to national security’ available at https://www. researchgate.net/publication/358398187_Of_Banditry_and_Human_Rustling_ The_Scourge_of_Kidnapping_in_Northern_Nigeria/link/62006375702c892ce f0ba4db/download (accessed 29 August 2022). See also IM Abbas ‘No retreat no surrender conflict for survival between Fulani pastoralists and farmers in Northern Nigeria’ (2013) 8 European Scientific Journal 17-18.

26. Goodluck Jonathan Foundation (2021). Terrorism and banditry in Northern Nigeria: the nexus (Katsina, Niger, and Zamfara States context. Abuja: Goodluck Jonathan Foundation).

27. C Okoli ‘Of banditry and human rustling: the scourge of kidnapping in Northern Nigeria’ (2022) 11 African Journal on Terrorism.

28. JC Akogwu ‘From terrorism to banditry: Mass abductions of schoolchildren in Nigeria’ Accord 19 August 2022 https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/from-terrorism-to-banditry-mass-abductions-of-schoolchildren-in-nigeria/ (accessed 14 September 2022).

29. Politicsandlifestyle, ‘Check out the 15 differences between terrorists and bandits as highlighted by Senator Sheu sanni’, https://ng.opera.news/ng/en/politics/18 (accessed 13 September 2022).

33. See Politics and lifestyle, ‘Check out the 15 differences between terrorists and bandits as highlighted by Senator Sheu sanni’ https://ng.opera.news/ng/en/politics/18 (accessed 13 September 2022).

34. See https://balkaninsight.com/2024/10/14/reversing-youth-exodus-from-west ern-balkans-will-be-hard-report-warns/ (accessed 20 October 2024), https://youth.europa.eu/news/eu-youth-strategy-2019-2027-proves-effective-addressing -young-peoples-concerns_en (accessed 20 October 2024).

35. T Hartsoe ‘Why people join terrorist groups’ Duke Today 23 January 2018 https://today.duke.edu/2018/01/why-people-join-terrorist-groups (accessed 13 Sep-tember 2022).

36. European Institute of Peace, ‘why do people join terrorist organisations?’ 29 June 2015 https://www.eip.org/why-do-people-join-terrorist-organisations/ (accessed 13 September 2022).

37. SB Grant ‘The understanding of evil: a joint quest for criminology and theology’ in R Chairs & B Chilton (eds) Star Trek visions of law & justice (2003).

38. G Martins ‘Types of terrorism’ available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316220694 (accessed 28 August 2022). Terrorism typologies refer to shared characters or traits exhibited by the terror groups involved in these violent crimes.

40. J Fallows, P Bergen, B Hoffman & S Simon ‘Al Qaeda then and now’ in KJ Greenberg (ed) Al Qaeda now: understanding today’s terrorists (2005) 3-26.

41. PS Fosl ‘Anarchism and authenticity, or why SAMCRO shouldn’t fight history’ In G A Dunn & JT Eberl (eds) Sons of anarchy and philosophy: brains before bullets (2013) 201-214.

42. AH Cordesman Terrorism, asymmetric warfare, and weapons of mass destruction: defending the US homeland (2002) referred to by Martins (n 38).

44. See ‘Terrorism’ referred to by Nicole Gutierrez, available at https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/terror (accessed 27 August 2022).

45. N Gutierrez ‘Four types of terror 1’ available at https://www.academia.edu/41467283/FOUR_TYPES_OF_TERROR_1 (accessed 30 August 2022).

46. Africa Centre for Strategic Studies referred to by Bridget Boakye, ‘Terrorism in Africa: 21 active militant groups on the continent in 2018’ https://face2 faceafrica.com/article/terrorism-in-africa-21-active-militant-groups-on-the-con tinent-in-2018 (accessed 30 August 2022).

47. See The Global Terrorism Index: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2022/03/05/the-worlds-centre-of-terrorism-has-shifted-to-the-sahel (accessed 20 October 2024); The United Nations Counter-Terrorism Office: https://www.un.org/counterterrorism/ (accessed 20 October 2024).

48. A Berko & E Erez ‘Gender, Palestinian women, and terrorism: women’s liberation or oppression?’ (2017) 30 Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 511.

49. A Speckhard & K Akhmedova ‘The new Chechen jihad: militant wahhabism as a radical movement and a source of suicide terrorism in post-war Chechen society’ (2006) 2 Democracy and Security 110.

50. EC Gentry & L Sjoberg Beyond mothers, monsters, whores: thinking about women’s violence in global politics (2015) 2.

52. T Agara ‘Gendering terrorism: women, gender, terrorism and suicide bombers’ (2015) 5 International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 116.

53. A Schmid & A Jongman Political terrorism (1988) 53; J Poland Understanding terrorism: groups, strategies, and responses (1988).

54. G Ammerdown ‘Rethinking security: a discussion paper’ (2016) https://www. rethinkingsecurity.org.ukCurott (accessed 1 September 2022).

55. Joint Counter Terrorism Team ‘Involvement of minors in acts of terrorism’, available at https://www.dni.gov/files/NCTC/documents/jcat/firstresponders toolbox/62us--Involvement-of-Minors-in-Terrorist-Plots-and-Attacks-Likely-To-Endure-survey.pdf (accessed 30 August 2022).

58. A Al-Bahri ‘How terror group recruits and lures children to specialized fighting camps’ https://abcnews.go.com/International/terror-group-recruits-lures-child ren-specialized-fighting-camps/story?id=24430928 (accessed 1 September 2022).

59 ‘When I arrived at the camp, fighters and religious teachers from the organization supervised our training’ Mohammed says. ‘The training was divided into two parts. In religious classes, they taught us their version of Islam, the extremist methods they follow, and the necessary foundations of creating an Islamic caliphate state - their ultimate goal. They also try to convince us of jihadist ideology, like the greatness of martyrdom.’

The second part of training is for combat. ‘They trained us very harshly,’ he said. ‘They trained us to deal with being tired and to face hardship. They also trained us to use arms’. Yasser’s father said officials from the militant group had tricked him into bringing his son to the camp by telling him it was merely for studying the Quran and foundations of Islam. But when his son arrived, ‘It turned out to be a camp to recruit children to be a new generation of extremists. They were trying to prepare children to carry out martyr bombings on behalf of the organization. I did not accept that and tried to pull Yasser out of the camp, but they refused and

59. prevented me from seeing him. They even threatened to execute me for attempting to prevent jihad.’ Abou al-Ghanem, an ISIS fighter who trains children in the camps, says that his organization creates them merely ‘to fulfill the duty upon us all to fight the enemy and learn the foundations of jihad and the true teachings of Islam’. He stated further ‘We are teaching children who are less than 15 years old how to fight and use arms in order to build a generation of strong fighters who follow the righteous path’ he says. ‘That’s why we created these camps’.

60. UNICEF document https://www.unicef.org/protection/children-recruited-by-armed-forces (accessed 1 September 2022).

61. I Afshan Abbasi & M Kumar Khatwan ‘An overview of the political theories of terrorism’ (2014) 19 OSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 103-107.

62. CP Blamires & P Jackson (eds) World fascism: a historical Encyclopedia Volume 1:A-K (2006): D Rapoport ‘Fear and trembling: terrorism in three religious traditions’ (1984) 78 American Political Science Review 668-672.

63. D Rapoport & A Yonah (eds) The morality of terrorism: religious and secular justification (1982); G Caforio Handbook of the sociology of the military, handbooks of sociology and social research (2006) 12.

64. A Zalman ‘History of terrorism: anarchism and anarchist terrorism, about news’ http://terrorism.about.com/od/originshistory/a/Anarchism.htm (accessed 1 September 2022).

65. M Banuin, quoted by I Abbasi & M Kumar Khatwani in ‘An overview of the political theories of terrorism’ (2014) 19 IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 103-107.

66. Blamires & Jackson (n 62); D Rapoport & A Yonah (eds) The morality of terrorism: religious and secular justifications (1982).

67. J Płaczek defines the concept of economic security of a state as ‘[...] such a state of development of the national economic system that ensures high efficiency of its functioning and the ability to effectively oppose external pressures that may lead to disturbances to its development. It aims to protect economic development’. Vide: J. Płaczek, the place and role of economic security in the security system of a state, in: TJemioło, sc. superv., Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem narodowym [Managing national security], part 1, Warsaw 2006, p. 113.

68. SB Grant ‘The understanding of evil: a joint quest for criminology and theology’ in R Chairs & B Chilton (eds) Star Trek visions of law & justice (2003).

70. S McGraw-Hill ‘Anarchism, terrorism studies and Islamism’ (2010) 1 Global Discourse 66-85; see also RB Fowler ‘The anarchist tradition of political thought’ (1972) 25 Western Political Quarterly 743-744.

73. The Assassination of Lord Mountbatten by IRA, ‘Facts and ...’ https://www. history.com/news/mountbatten... (accessed 1 September 2022).

74. The Guardian online news of 28 November 2020, ‘Boko Haram kill dozens of farm workers in Nigeria’ available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/28/boko-haram-reported-to-have-killed-dozens-of-farm-workers-in-nigeria (accessed 1 September 2022).

75. The Guardian news ‘At least 300 people killed and hundreds seriously injured in attack blamed on militant group al-Shabaab’ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/15/truck-bomb-mogadishu-kills-people-somalia (accessed 1 Sep-tember 2022).

77. See UK Foreign Travel Advice, https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/algeria/terrorism (accessed 14 September 2022).

78. UNHCR (March 2019). ‘Country operation update - Burkina Faso’. UNHCR available at https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/03/22/we-found-their-bodies-later-day/atrocities-armed-islamists-and-security-forces (accessed 1 September 2022).

79. Aljazeera News 3 June 2022 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/13/at-least-50-killed-in-burkina-faso-rebel-attack-government (accessed 14 September 2022).

80. Sophie Garcia, Aljazeera News 10 June 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/10/attackers-kill-11-military-police-in-burkina-faso (accessed 14 June 2022).

81. Global fight against terrorism, ‘Gunman kills at least 20 people at Sudan mosque’ https://www.gfatf.org/archives/gunman-kills-least-20-people-sudan-mosque/ (accessed 14 September 2022).

82. Global Fight Against Terrorism, ‘Sudan PM says survived terror attack in capital’ https://www.gfatf.org/archives/survived-terror-attack-capital/ (accessed 14 Sep-tember 2022).

83. UK Gov, ‘Foreign travel advice Angola’ https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/angola/terrorism (accessed 14 September 2022).

84. As above; Land Mine and Munition Monitor http://archives.the-monitor.org/index.php/publications/display?url=lm/2002/angola.html (accessed 13 Sep-tember 2022).

85. SBM Intelligence 2020, ‘The Economics of the Kidnap Industry in Nigeria, Lagos’, https://www.sbmintel.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/202005_Nigeria-Kidnap.pdf (accessed 14 September, 2022).

86. U William ‘Insecurity: N10 billion demanded in kidnapping ransoms in H1 2021-SBM’, Naira Metrics, 12 July 2021, https://nairametrics.com/2021/07/12/insecurity-n10-billion-demanded-in-kidnapping-ransoms-in-h1-2021-sbm (accessed 14 September 2022).

87. D Daniel ‘Kidnapping grows as Nigerians pay N650 million ransom in 1 year’ https://www.naijaloaded.com.ng/news/kidnapping-grows-as-nigerians-pay-n650-million-ransom-in-1-year (accessed 13 September 2022).

88. CA Odinkalu ‘Banditry in Nigeria - a brief history of a long war’ International Centre for Investigative Reporting 27 December 2018 https://www.icir nigeria.org/banditry-in-nigeria-a-brief-history-of-a-long-war/ (accessed 14 Sep-tember 2022).

92. Art 3 specifically states: ‘In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration’.

93. It provides: ‘States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child’.

94. See sec 1 of the Act which states: ‘In every action concerning a child, whether undertaken by an individual, public or private body, institutions or service, court of law, or administrative or legislative authority, the best interest of the child shall be the primary consideration’.

95. This section can also be said to apply to the recruitment of children into any form of armed conflict including terrorism and banditry.

97. By virtue of sec 2, where death occurred in the course of the hostage taking, the crime shall be punishable with death.

98. M Melnick ‘Why are terrorists so often young men?’ https://www.huffpost.com/entry/terrorists-men-violent-biology-boston-marathon_n_3117206 (accessed 1 September, 2022) See also T Tsarnaev ‘Why are terrorists so often men?’ available at https://www.salon.com/2013/04/25/why_are_terrorists_so_often _men/ (accessed 1 September 2022).

99. Terrorism (Prevention) Act 2011.

100 Sec 11. This section deals directly with instances of banditry as we have it today in Nigeria and across other African countries. This provision further buttresses our

100. argument earlier that banditry which is akin to hostage taking is a shade or arm of terrorism. Evidence has shown from the accounts of victims of banditry or kidnapping that just like the terrorist, the bandits/kidnappers are usually armed with sophisticated weapons, kill, destroy properties of their victims like cars and gadgets, threaten and have severally told their victims that they are terrorists from one camp or the other.

101. US Department of States ‘Country reports on terrorism 2020: Algeria’ https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2020/algeria/ (accessed 15 September 2022), see also Tony Nyiam ‘Why Nigerian armed forces can’t fight terrorism’ Vanguard News 8 August 2020 https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/08/why-nigerian-armed-forces-cant-fight-terrorism-tony-nyiam/ (accessed 1 September 2022).

102. International Crisis Group ‘Violence in Nigeria’s north west: rolling back the mayhem’ 18 May 2020, referred to by JS Ojo and others ‘Forces of terror: armed banditry and insecurity in North-west Nigeria’ (2023) 19 Journal of Democracy and Security 4.